Jesus’ genealogies are frequently said to be irreconcilable. They are not. They are an invitation to delve deeply into the history of both Israel and her Messiah, intended not to mystify but to edify.

Guest blog by James Bejon

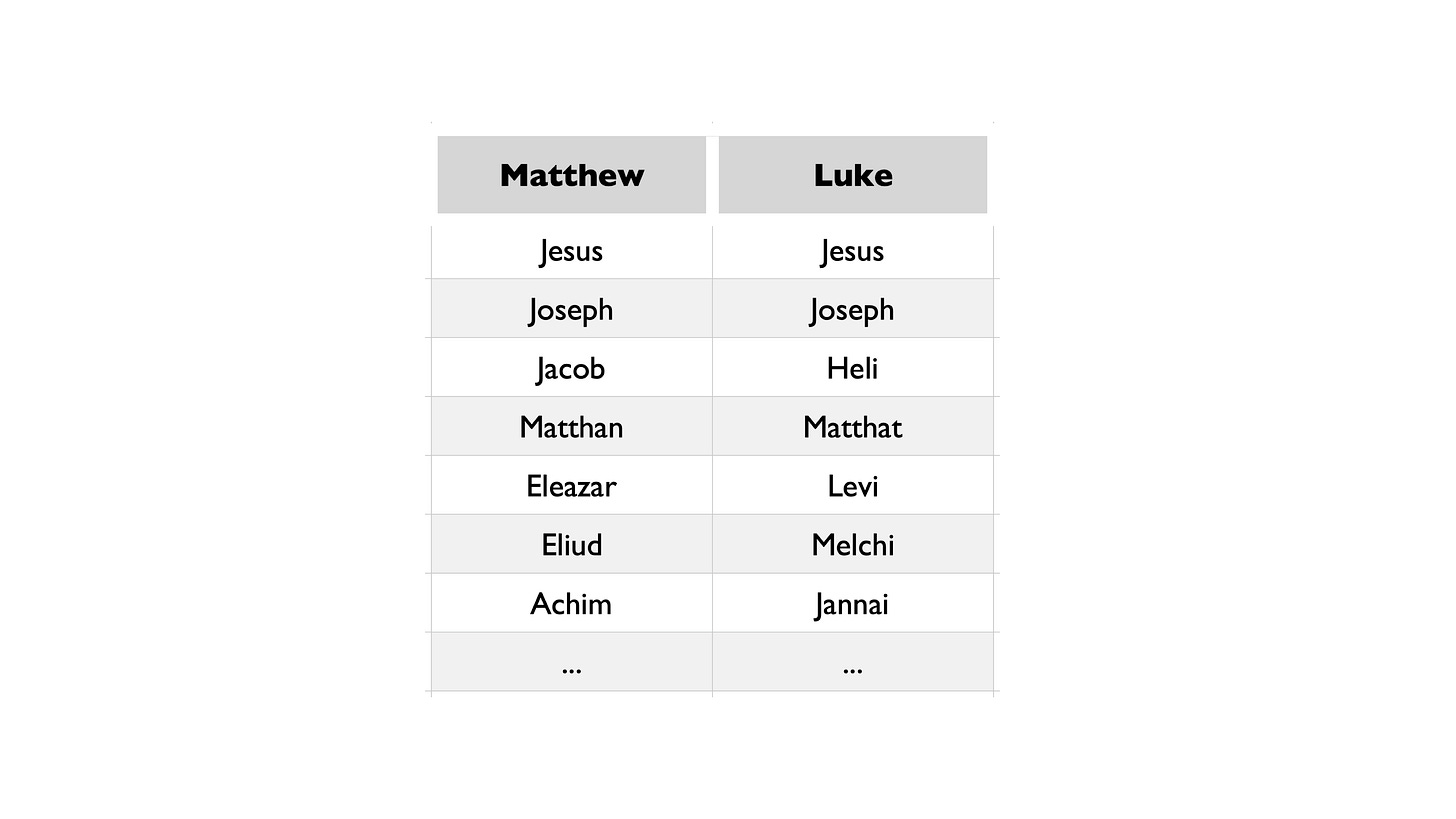

The New Testament attributes two different genealogies to Jesus. One is found in the Gospel of Matthew, the other in the Gospel of Luke. These genealogies have long been a point of contention among adherents of Christianity and Judaism. Many Rabbis take them to be irreconcilable. And, in a sense, I’m not surprised. Jesus’ genealogies certainly aren’t *easily* reconcilable. And so, to some extent, we can all agree.

But of course whether Jesus’ genealogies are *easily* reconcilable isn’t really the issue. All sorts of things in Scripture are hard to reconcile, such as the relationship between God’s sovereignty and man’s responsibility—or, more relevantly, between different genealogies in, say, Genesis and Chronicles (compare Genesis 46.21 with 1 Chronicles 7.6, 8.1+). And why shouldn’t they be hard to reconcile? God’s universe is a complex place (in case you hadn’t noticed), and to perpetuate your lineage in the ancient world was a fraught and often messy business (cp., for instance, Genesis 38). Furthermore, Scripture doesn’t claim to be easy to understand; what it claims to be is trustworthy and a source of truth and wisdom for those who study it with a desire to learn. In what follows, then, I’d like us to try to do just that—to study Jesus’ genealogies with a desire to find out what they teach us and then to see what it tells us about their coherence (or otherwise).

The Nature of the Problem

Matthan and Matthat could plausibly be different names for the same person, in which case we could suppose the same to be true of Jacob and Heli. (It’s not uncommon for Biblical characters to be known by multiple names.) Yet one can’t extend such logic indefinitely. To say that Heli is another name for Jacob is one thing, but to *also* say that Levi is another name for Eleazar, Eliud for Melchi, Achim for Jannai (etc.), seems a bridge too far. And there are other problems elsewhere in Jesus’ genealogy (which will be the focal point of the present article). What, then, to do?

Towards a Possible Solution

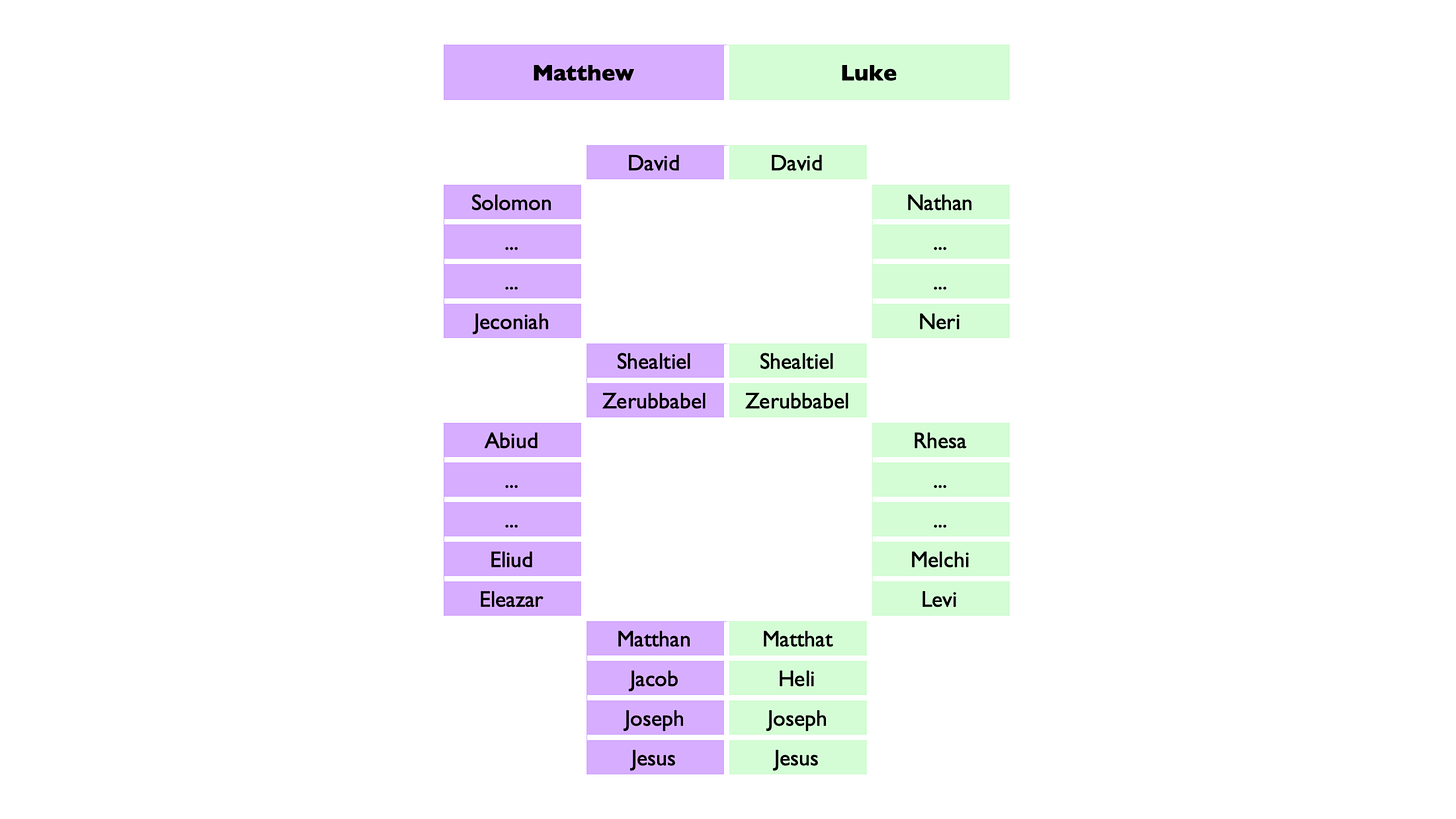

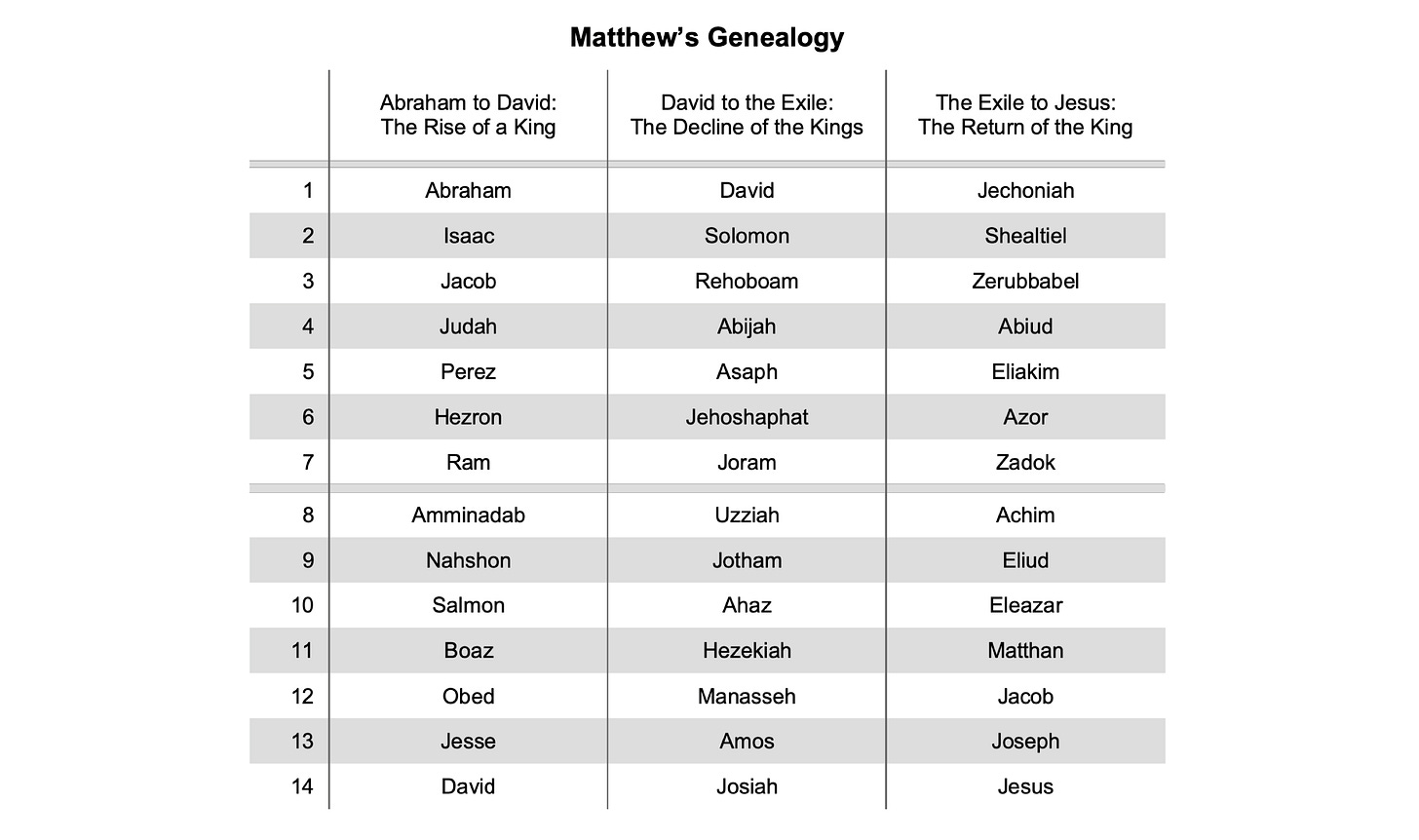

The first thing we should do is pause to notice a significant point of contact between Matthew and Luke’s genealogies. Matthew and Luke don’t trace Jesus’ genealogy from Matthan-aka-Matthat back to David via *completely* different routes. They share a point of contact at the time of the exile. Both Matthew and Luke tell us Matthan-aka-Matthat is the son of an individual named Zerubbabel, who is the son of Shealtiel. (After that, Matthew ascends the line of the kings, while Luke takes a back route.) And, since neither Zerubbabel and Shealtiel are common names (they’re each borne by only one person in the OT), Matthew and Luke’s Zerubbabel ben Shealtiel is no doubt the same person.

We can thus conceive of the relationship between Matthew and Luke as shown below. Matthew’s genealogy is coloured purple (since it’s the line of the kings: David, Solomon, Rehoboam, etc.), while Luke’s is coloured green(ish) (an offshoot from the stump of David: Isa. 11.1, 53.2).

So what about the differences between these genealogies? Some scholars view one genealogy as Joseph’s and the other as Mary’s. But, as Bart Ehrman points out, the text of Scripture doesn’t actually suggest *either* genealogy is Mary’s; rather, it traces both genealogies back through *Joseph* (Matt. 1.16, Luke 3.23). In any case, even if Matthew and Luke’s genealogies differed between Matthan-aka-Matthat and Zerubbabel because one of them was Mary’s, it wouldn’t explain why they differed between Shealtiel and David. For one reason or another, then, we need another explanation.

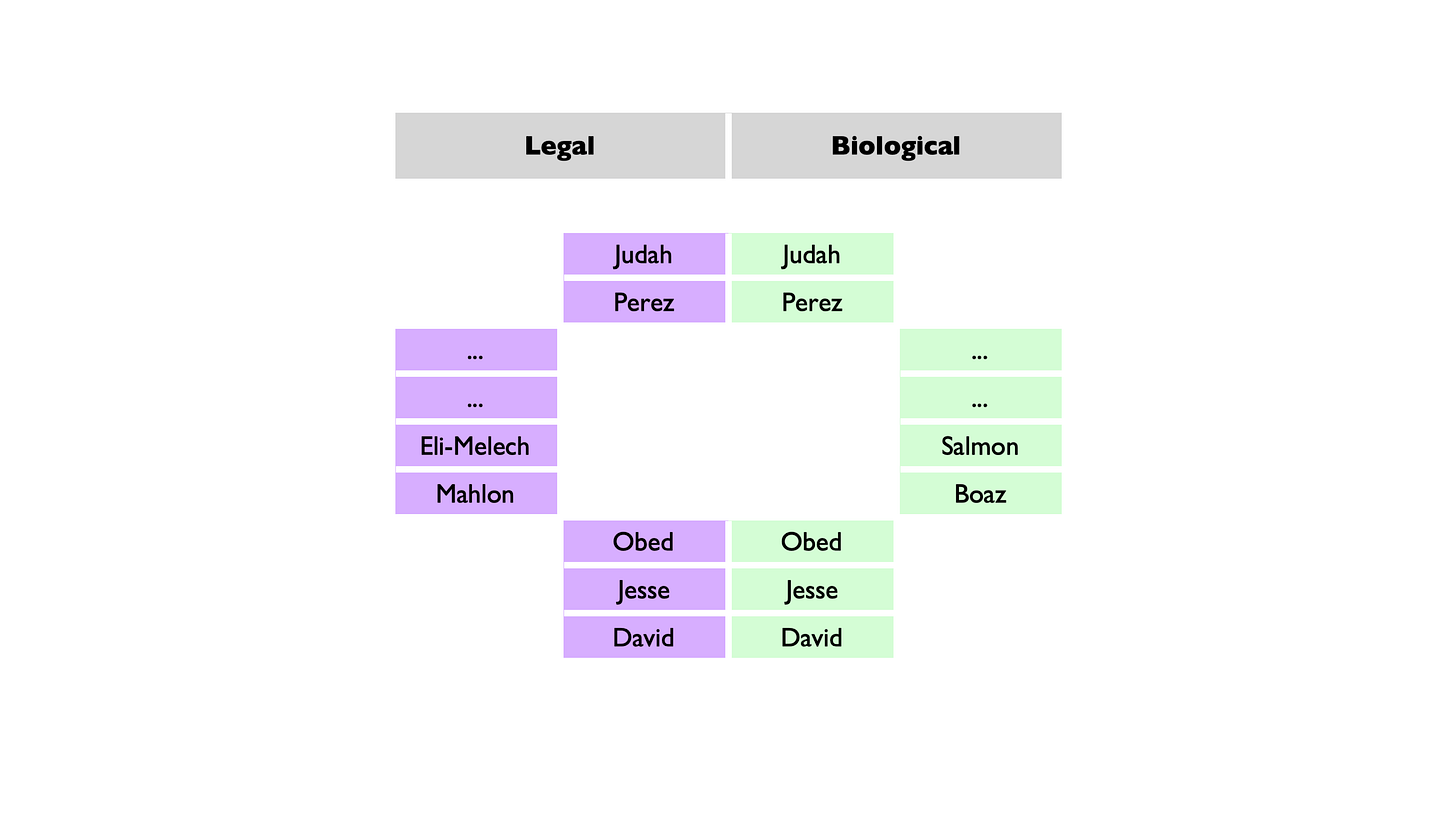

What else could explain why a person has two different genealogies? One possibility is a ‘levirate marriage’ (viz. a marriage of the kind described in Deut. 25). Consider the case of Boaz and Ruth. Due to Boaz’s (levirate) marriage to Ruth, Obed’s genealogy could be reckoned in two different ways. Boaz acquired Ruth as his wife in order to ‘perpetuate the name’ of Mahlon (Ruth 4.10), so Obed could legitimately be referred to as ‘a son of Mahlon, the son of Eli-Melech (etc.)’. Biologically, however, Obed was ‘the son of Boaz, the son of Salmon (etc.)’. As a result, Obed’s genealogy could be reckoned in two different ways, as shown below.

The question, then, is whether we have any reason to think *Jesus’* genealogy involved such events. And the answer is, Yes, we do. True, we don’t have an *explicit* reference to a levirate marriage or an adoption, but Jesus’ genealogy is marked out by five distinct oddities, which, considered as a whole, are suggestive of both a levirate marriage *and* an adoption event in Jesus’ past ancestry. Below, we’ll consider each oddity in turn.

Oddity #1: Jesus is a descendant of Jeconiah

Jeconiah’s father (Jehoiakim) lived a wanton life, and God chastised him for it (via the prophet Jeremiah). ‘Even if your son was a signet ring on my right hand’, God said, ‘I would still tear you off…and give you into the hand of Nebuchadnezzar!’ (Jer. 22.24). In other words, Jehoiakim’s time was up. Even if his son Jeconiah had been a saint (which he wasn’t), it couldn’t have redeemed his reign.1

God then went on to criticise Jeconiah himself. ‘Register this man as childless!’, God said to the Temple genealogists. ‘None of his seed are to succeed him on the throne of David!’ (Jer. 22.30). Not only, therefore, would Jeconiah’s father be exiled; Jeconiah’s descendants would lose their right to inherit the throne of David (due to their father’s sin).

To put the point mildly, then, the (Matthean) notion of a Messiah who arises from the line of Jeconiah is an awkward one. And its awkwardness isn’t an issue which critics of the Bible have had to draw our attention to; Matthew himself draws attention to it. In the very first verse of his Gospel, he introduces us to Jesus as the one who will fulfil God’s promise to King David, and, immediately afterwards, he sets out a record of Jesus’ ancestry which is selective in its inclusion of kings (Ahaziah, Joash, and Amaziah are excluded) and yet does not exclude Jeconiah; rather, it has him rise to prominence at a pivotal moment in history. Why?

Oddity #2: Despite Jeremiah’s curse, Jeconiah has descendants

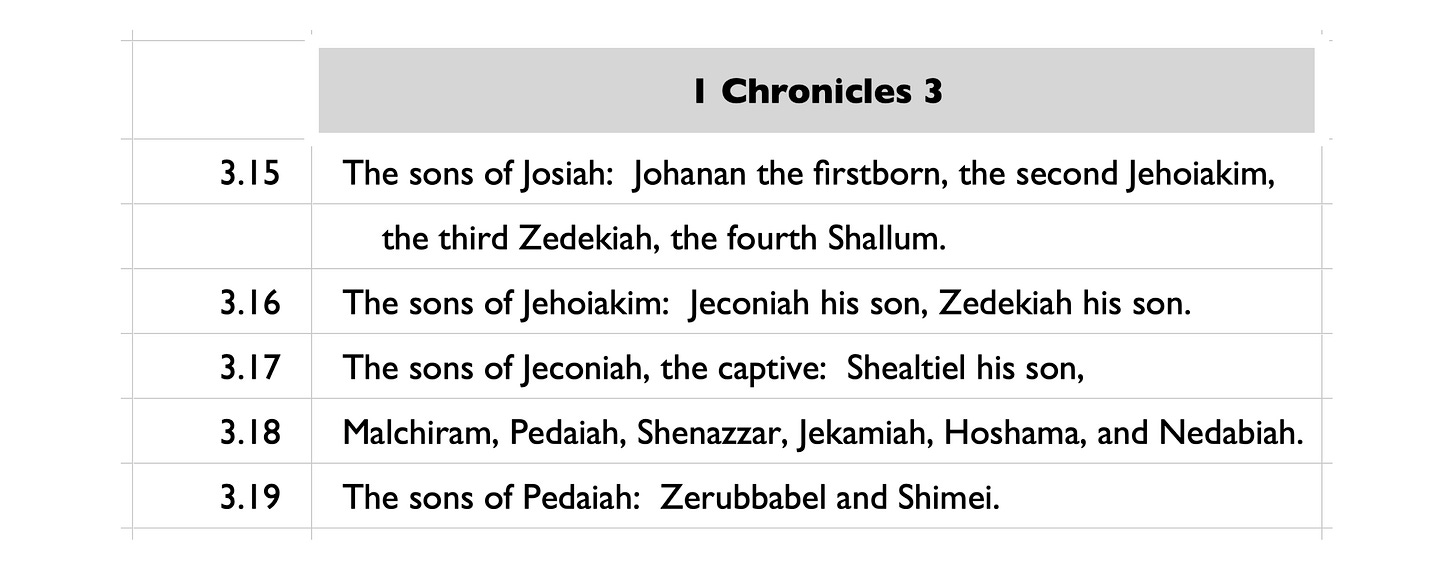

Despite the fact Jeconiah is rendered ‘childless’ by Jeremiah’s curse, 1 Chronicles 3’s king list credits him with seven sons—the ideal number (compare Ruth 4.15, Job 1.2, 42.13, Jer. 15.9). How come?

Oddity #3: Shealtiel is treated unusually in 1 Chronicles 3

Oddity #4: Zerubbabel is the product of a levirate marriage

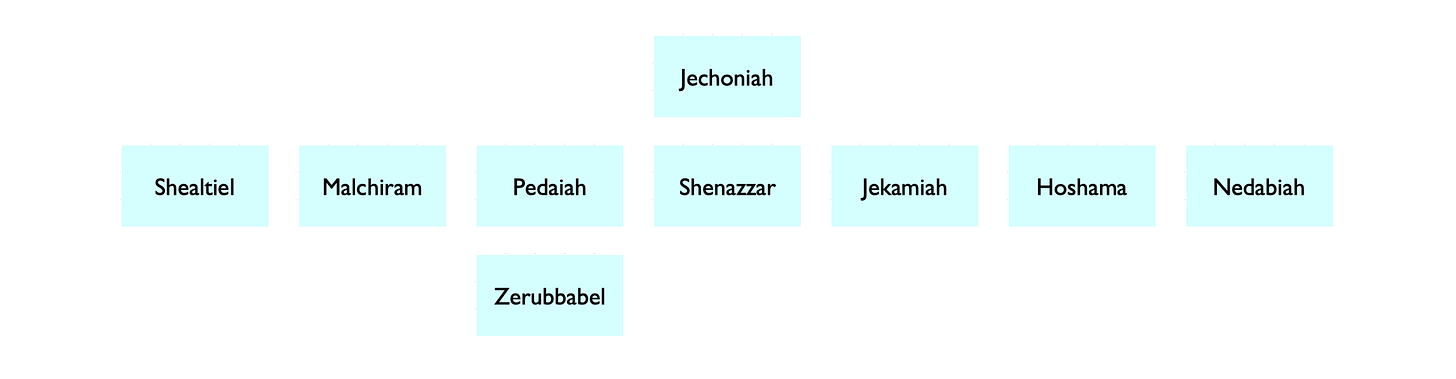

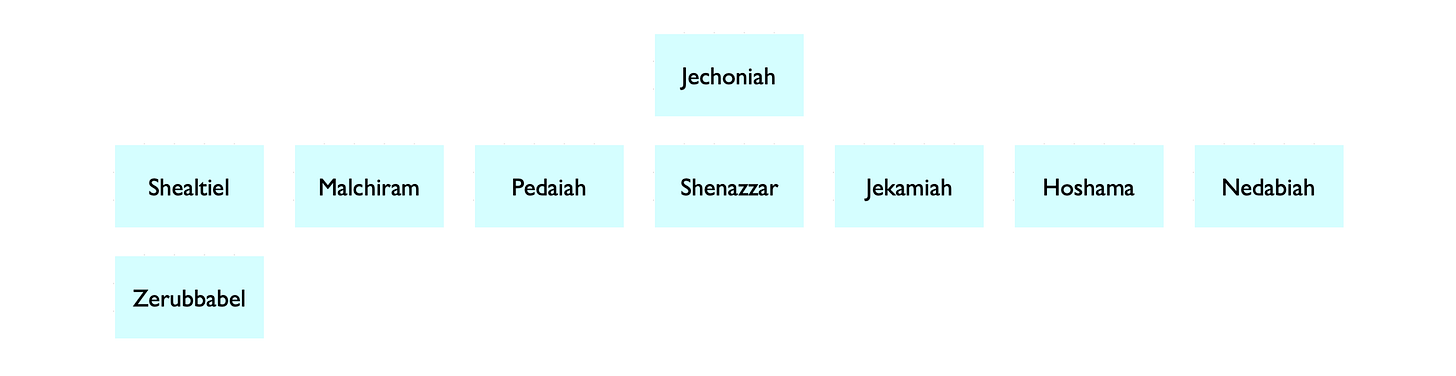

Recall the text of 1 Chronicles 3.17–19 (above). If we were asked to chart out Jeconiah’s family tree on the basis of 3.17–19, we’d probably come up with something like the tree shown below (cp. the text of 3.17–19 above).

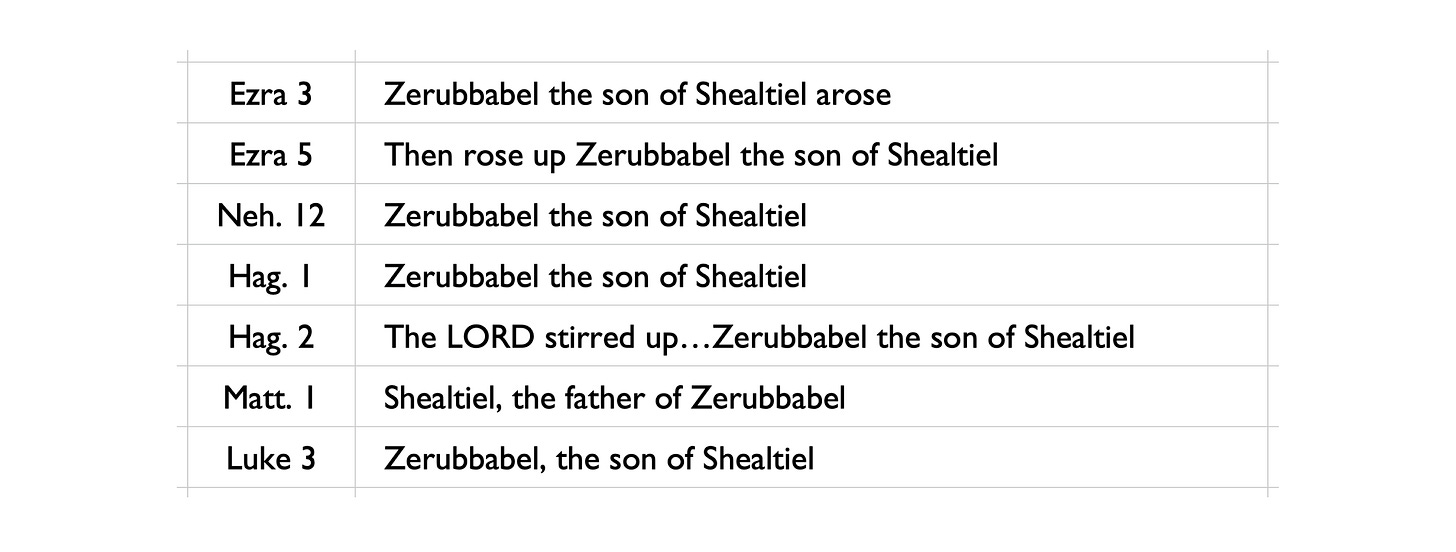

Yet, outside of 1 Chr. 3, Zerubbabel is never referred to as the son of Pedaiah; he’s invariably referred to as the son of *Shealtiel*.

Oddity #5: Zerubbabel is the son Jeconiah *should* have been

Only two people in Scripture are likened to signet rings—Jeconiah and Zerubbabel. In Jeremiah, Jeconiah is told he *should* have been like a signet ring on God’s right hand (but wasn’t). Then, after the exile, God says he’ll make Zerubbabel like a signet ring (Hagg. 2.23)—or perhaps even ‘like *the* signet ring’ (כַּחוֹתָם), which might subtly hint at his connection with Jeconiah. Either way, Zerubbabel will thus be what Jeconiah *should* have been.

We can sum up the above five oddities as follows:

1. Jesus is the descendant of Jeconiah—a man who is pronounced ‘childless’ and whose descendants have been disqualified from the throne of David.

2. Though pronounced childless, Jeconiah is said to have sons.

3. One of those sons—namely Shealtiel—is not like Jeconiah’s other sons (for an unstated reason).

4. Shealtiel’s son (Zerubbabel) is the product of a levirate marriage (or a similar arrangement).

5. Zerubbabel fulfils Jeconiah’s intended destiny (as a ‘signet ring’).

These oddities invite explanation, and, happily, they can be explained by a plausible historical scenario. The scenario consists of four components. The first is explicitly stated in Scripture; the rest can plausibly be inferred/hypothesised on the basis of Scripture.

Component #1: Jeconiah’s repentance

Although Jeconiah’s life began badly, Jeconiah came good in the end. Jeremiah called Judah’s kings not to resist the might of Nebuchadnezzar but to surrender to him (in which case both their lives and their land would be spared: Jer. 21.8+), and Jeconiah did so (2 Kgs. 24.12). Rather than stay and fight, he handed himself over to Nebuchadnezzar, and Nebuchadnezzar spared his life, just as God said he would (cp. Jer. 52.31+). Indeed, God gave him great favour in Nebuchadnezzar’s eyes. On a Babylonian ration tablet (dated to the year 591 BC), Jeconiah is assigned over six times as large a quantity of rations of anyone else on the tablet. Moreover, although Jeconiah later ended up in prison, God raised him up, which is the note on which Jeremiah’s prophecies conclude.

Component #2: God’s repentance

When Jeconiah repented, God repented—that is to say, God rescinded Jeremiah’s prophecy against Jeconiah. That God rescinded Jeremiah’s prophecy is not stated explicitly in the text of Jeremiah, but it is a hypothesis which would explain both the reference to Jeconiah’s sons in Chronicles as well as the reference to Zerubbabel as a ‘signet ring’ in Haggai. In addition, it would be thoroughly consistent with the flow and tenor of Jeremiah’s prophecies. Throughout the book of Jeremiah, where there is repentance, there is hope, even when it seems as if the die has already been cast (e.g., Jer. 7.5+, 17.24+, 22.4+, etc.). When a nation changes its ways, God changes its destiny (18.1+). And so, when Jeconiah handed himself over to Nebuchadnezzar, God may well have done likewise (a point we’ll pick up later). Indeed, when Jeconiah surrenders to Nebuchadnezzar, God explicitly identifies him as one of the ‘good figs’ who were to be ‘planted’ and ‘built up’ in Babylon, all of which flows on from God’s promise to raise up a righteous branch from the line of David (23.5+).

Component #3: Shealtiel’s adoption

In exile, Jeconiah fathered six sons and adopted a seventh named Shealtiel (hence Matthew and the Chronicler situate Shealtiel’s ‘birth’ after the exile),2 which explains why Shealtiel is singled out in the text of 1 Chronicles 3.17–18. Shealtiel wasn’t like Jeconiah’s other sons; his ‘birth/sonship’ was highly significant. (The name ‘Shealtiel’ may even mean ‘I borrowed him’.)

That Shealtiel was adopted is not an insignificant detail (if Shealtiel was in fact adopted). When God rescinds a curse, he doesn’t simply pretend it was never uttered; he provides a *basis* on which it can be subverted/redirected. For instance, Nineveh might not have been ‘overthrown’ (nehefechet), but it can certainly be said to have been nehefechet in a different sense (‘converted’) (Jonah 3). And not all those who have sinned have received the wages of sin (death), yet death has certainly been the consequence of their sin (Rom. 6).

God seems to have subverted/undone Jeconiah’s curse in a similar manner. Since Shealtiel was adopted into Jeconiah’s line, he had both a legal/adopted genealogy and a biological genealogy. And these two genealogies are precisely what we find set out in Matthew and Luke respectively. Matthew connects Shealtiel back to David via the Judahite kings (Shealtiel’s legal line), while Luke connects him back to David via his biological line—a lesser known branch of David’s family tree (cp. Luke 3.31 w. 1 Chr. 3.5, Zech. 12.12). By means of Shealtiel’s adoption, then, God enabled Judah’s royal line to be continued: Shealtiel was not literally ‘of the seed’ of Jeconiah, so he could be deemed immune to Jeconiah’s curse, and yet Shealtiel could legitimately continue Jeconiah’s line, since he was a son of David. And, in case anyone wondered if it was appropriate for a merely legal descendant of Jeconiah to continue the line of Judahite kings, God added a further layer of complexity into the equation, as we’ll now consider.

Component #4: Zerubbabel’s ancestry

Since Shealtiel died before he could father any children, one of Jeconiah’s biological sons (Pedaiah) fathered a child for him, namely Zerubbabel. Zerubbabel was not merely, therefore, a legal descendant of Judah’s last king, Jeconiah; he was also his biological descendant (via Pedaiah), and yet he was shielded from Jeconiah’s curse by virtue of his membership of Shealtiel’s family tree. Zerubbabel was thus a remarkable individual—a ‘seed of Babylon’ by name, a seed of David by biological descent (per Luke’s genealogy), a descendant of Judah’s last king by adoption (per Matthew’s genealogy), and the man under whose headship God chose to lead his people back from exile. In and through Zerubbabel’s rise, then, God fulfilled his promise to Jeremiah: he regathered his flock, assigned faithful shepherds over them (Zerubbabel and Jeshua), and in the process raised up a righteous branch from David’s progeny (Jer. 23.1–8).

Assessment

First, it undercuts the claims of those who say Jesus’ genealogies are irreconcilable. Specifically, it proffers a way to read Jesus’ genealogies which: a] is at least possible (and perhaps even plausible), b] doesn’t entail any contradictions, and, importantly, c] takes its cue not from a preconceived notion about how Matthew and Luke *should* have documented Jesus’ ancestry, but from a series of clues embedded in the text of Scripture itself.

Second, it suggests Jesus’ genealogies are credible accounts of Jesus’ ancestry. Jesus’ genealogies exhibit the kind of complexity one might reasonably expect to encounter in a pair of 2,000-year-long genealogies, and they become most complex where one would expect them to, i.e., in Babylon, at a tumultuous time in Judah’s history. By extension, then, we needn’t be too worried about the discrepancies in the inter-testamental stretch of Jesus’ genealogy (i.e., between Shealtiel and Joseph). The text of Scripture provides us with a considerable amount of information about Jeconiah’s family tree, and that information makes good sense of the discrepancies entailed in Shealtiel’s ancestry; consequently, it doesn’t seem unreasonable to view the discrepancies entailed in Joseph and Mary’s ancestries—about which we know nothing apart from what Matthew and Luke tell us—in a similar light (i.e., to assume more information would clarify matters).

Third, it helps us grasp the *purpose* of Jesus’ genealogies in the context of the New Testament. Matthew draws our attention to Jeconiah for a reason. At the start of the final stretch of Matthew’s genealogy, God brought redemption to a cursed line by Jeconiah’s adoption of a son, which is exactly what he did at the end of it: by Joseph’s adoption of Jesus, God brought redemption to an entire race.

Meanwhile, Luke draws our attention *away* from Jeconiah, and he too has his reasons. Just as in Jeconiah’s day God raised up a lesser known branch of David’s family tree to replace Judah’s failed leaders, so in and through Jesus’ ministry God raised up various unknown Israelites to do likewise (Luke 1–2).

Matthew and Luke’s genealogies also resonate with the introduction to their Gospels in a further way. Matthew has Jesus immediately come into conflict with Herod, since, as a son of Jeconiah, Jesus is a rightful heir of David’s throne (and Herod is not). Meanwhile, Luke has Jesus raised in obscurity and born a ‘holy child’, since Jesus is not only a son of Jeconiah; he is also a member of a lesser known Davidic line which has been shielded from Jeconiah’s curse.

As such, Matthew and Luke’s genealogies constitute the perfect introductions to their respective Gospels, not despite their oddities, but because of them. At the same time, they give us a reason to have confidence in the New Testament’s record of Jesus, even when it might seem at first blush to be difficult to process. Like God himself, the text of Scripture rewards those who persevere.

James Bejon is a researcher at Tyndale House. This article is originally from his Thoughts on Scripture substack and used with permission.

- Jer. 36.30 complicates things–more on that some other time.

- Shealtiel is a son of ‘Jeconiah the captive’.